Dad owned a grocery. I had worked for him in the family grocery store since I was 12 – earning 25 cents and hour. I noticed that I wasn’t getting it all and, upon questioning, found out that something called social security was being taken out. I didn’t know what social security was, but I didn’t like it.

However, Dad sold the store in about 1946 and bought a farm when I was 15. He also farmed my brother Dick’s farm that he had bought as he left the Navy after WWII. Dad loved farming and I didn’t. Afterwards, I then worked for the man who had bought him out at the country store. It may have been someone named Weber.

During World War 2, when it was difficult to find help, my sister, Emmalu – whose husband was in the Army – and I picked cotton one fall for our dad. School closed for “cotton picking”. I hated it. It was hot. It was hard work. Worst of all, one got dirty! Sister was a go-getter. I remember that we would take four rows at a time. Sister would pick her two rows and would help me with my two rows. I’m sure that I was a mixed blessing; however, I got paid what I was worth because cotton pickers got paid by the pound. I didn’t get rich.

I left home in the summer of 1948 for the University of Oklahoma. I went to summer school every summer until 1951 so that I wouldn’t have to work on the farm.

I had just finished my junior year, and I came to the decision that my father was really a nice guy. I regretted that I had never spent a summer helping him. As a result, I decided that I should skip summer school and go home and help.

The first day, at 6:00 a.m., he put me on the Ford tractor on the Boggy Creek farm. (In those days, there were no enclosed cabs on tractors, no shade, no radios, no colored glasses, and it was years before closed cabs with air conditioning, TVs and DVDs,) As I plowed a row, a lot of dust (dirt) was stirred up and when I turned around at the end of the row, I met that dust on my return. Row after row after row, I met my dust, and the individual dusts collected into what was a dust conspiracy. It was awful! To top off the misery was the hot sun which unrelatedly found its way even through the dust. Oh, for a cloud – but they never seemed to find me. I sang every song that I knew, I quoted every line of poetry that Miss Hudson, my high school English teacher, had made me learn, I thought every thought that I could retrieve from my brain, looked at my watch and it was only 7 o’clock in the morning! Alas, only twelve more hours to go. Multiply 13 hours a day by eighty-nine more days to go – 1,157 hours of hard work was before I could return to the University of Oklahoma. Oh – and there was no one to hear me except the jackrabbits, and one lonely coyote.

The first day, at 6:00 a.m., he put me on the Ford tractor on the Boggy Creek farm. (In those days, there were no enclosed cabs on tractors, no shade, no radios, no colored glasses, and it was years before closed cabs with air conditioning, TVs and DVDs,) As I plowed a row, a lot of dust (dirt) was stirred up and when I turned around at the end of the row, I met that dust on my return. Row after row after row, I met my dust, and the individual dusts collected into what was a dust conspiracy. It was awful! To top off the misery was the hot sun which unrelatedly found its way even through the dust. Oh, for a cloud – but they never seemed to find me. I sang every song that I knew, I quoted every line of poetry that Miss Hudson, my high school English teacher, had made me learn, I thought every thought that I could retrieve from my brain, looked at my watch and it was only 7 o’clock in the morning! Alas, only twelve more hours to go. Multiply 13 hours a day by eighty-nine more days to go – 1,157 hours of hard work was before I could return to the University of Oklahoma. Oh – and there was no one to hear me except the jackrabbits, and one lonely coyote.

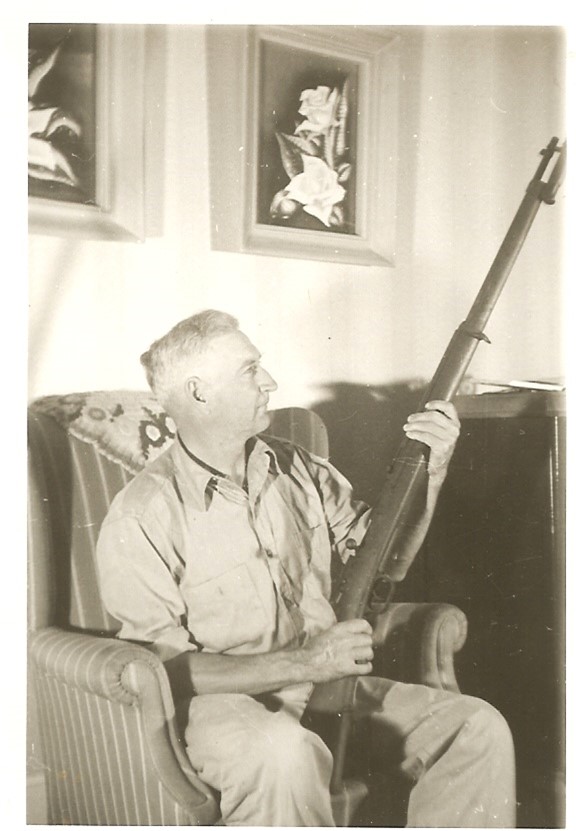

On the Red River farm, we built a fence. About 3 hours later, the cattle spooked for some reason, stampeded, and tore down part of the fence. We had to rebuild it. As we were working, we came across a rattlesnake. I pinned it down and Dad beat it to death. This farm had a rattlesnake den. As they came out to sun, Dad would practice shooting them with his new pistol that we children gave him for Christmas.

For the rest of the summer, I ate my lunch on the tractor.

At the end of the day, it was necessary to take at least 3 baths to get clean – we didn’t have a shower. The water was so hard, that regular soap curdled, requiring Vel dishwashing soap. The routine was to take a bath, drain the water making sure that the dirt went down the drain. Repeating this two more times, I felt that I was clean again. Even if my Dad was still a nice guy, my regret left me at the end of that first day. Oh, for the university!

I’m sure that I was mouthy about my dislike of every hour I spent on the farm, but to my father’s everlasting credit – and patience – he never said a “mumbling” word about what he thought of my help that summer. Since I wasn’t paid, I can say for sure that I was worth it!